Two

of the world’s largest drug companies are paying hundreds of millions of

dollars to doctors every year in return for giving their patients anemia

medicines, which regulators now say may be unsafe at commonly used doses.

The

payments are legal, but very few people outside of the doctors who receive

them are aware of their size. Critics, including prominent cancer and kidney

doctors, say the payments give physicians an incentive to prescribe the

medicines at levels that might increase patients’ risks of heart attacks or

strokes.

Industry

analysts estimate that such payments — to cancer doctors and the other big

users of the drugs, kidney dialysis centers — total hundreds of millions of

dollars a year and are an important source of profit for doctors and the

centers. The payments have risen over the last several years, as the makers of

the drugs, Amgen and Johnson & Johnson, compete for market share and try

to expand the overall business.

Neither

Amgen nor Johnson & Johnson has disclosed the total amount of the payments.

But documents given to The New York Times show that at just one practice in

the Pacific Northwest, a group of six cancer doctors received $2.7 million

from Amgen for prescribing $9 million worth of its drugs last year.

Yesterday,

the Food and Drug Administration added to concerns about the drugs, releasing

a report that suggested that their use might need to be curtailed in cancer

patients. The report, prepared by F.D.A. staff scientists, said no evidence

indicated that the medicines either improved quality of life in patients or

extended their survival, while several studies suggested that the drugs can

shorten patients’ lives when used at high doses. Yesterday’s report

followed the F.D.A.’s decision in March to strengthen warnings on the

drugs’ labels.

The

report was released in advance of a hearing scheduled for tomorrow, during

which an F.D.A. advisory panel will consider whether the drugs are overused.

The

medicines — Aranesp and Epogen, from Amgen; and Procrit, from Johnson &

Johnson — are among the world’s top-selling drugs, with combined sales of

$10 billion last year. In this country, they represent the single biggest drug

expense for Medicare and are given to about a million patients each year to

treat anemia caused by kidney disease or cancer chemotherapy.

Dr.

Len Lichtenfeld, the deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer

Society, said that both patients and doctors would benefit from fuller

disclosure about the payments and the profits that doctors can make from them.

“I suspect that Medicare is going to take a very careful look at what is

going on here,” he said.

Still,

the anemia drugs can help patients’ quality of life, when used appropriately,

he said. “We shouldn’t condemn every oncologist; we shouldn’t condemn

the drugs, because of the situation we’re in now.”

Federal

laws bar drug companies from paying doctors to prescribe medicines that are

given in pill form and purchased by patients from pharmacies. But companies

can rebate part of the price that doctors pay for drugs, like the anemia

medicines, which they dispense in their offices as part of treatment. The

anemia drugs are injected or given intravenously in physicians’ offices or

dialysis centers. Doctors receive the rebates after they buy the drugs from

the companies. But they also receive reimbursement from Medicare or private

insurers for the drugs, often at a markup over the doctors’ purchase price.

Medicare

has changed its payment structure since 2003 to reduce the markup, but private

insurers still often pay more. Combined with those insurance reimbursements,

the rebates enable many doctors to profit substantially on the medicines they

buy and then give to patients.

The

rebates are related to the amount of drugs that doctors buy, and physicians

that agree to use one company’s drugs exclusively typically receive higher

rebates.

Johnson

& Johnson said yesterday in a statement that its rebates were not intended

to induce doctors to use more medicine. Instead, the rebates “reflect

intense competition” in the market for the drugs, the company said.

Amgen

said that rebates were a normal commercial practice and that it had always

properly promoted its drugs.

“Amgen

is dedicated to patient safety,” said David Polk, a spokesman. “We believe

our contracts support appropriate anemia management and our product promotion

is always strictly within the label.”

Both

companies’ stocks fell yesterday after release of the F.D.A. report. Amgen

executives may face questions about the controversy from investors today when

the company holds its annual meeting in Providence, R.I.

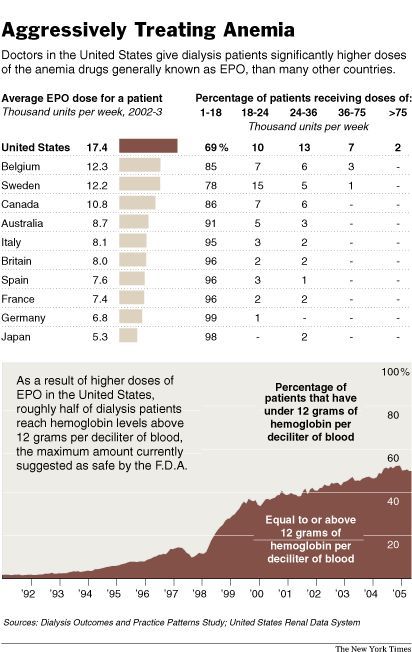

Since

1991, when the first of the drugs was still relatively new, the average dose

given to dialysis patients in this country has nearly tripled. About 50

percent of dialysis patients now receive enough of the drugs to raise their

red blood cell counts above the level considered risky by the F.D.A.

American

patients receive far more of the anemia drugs than patients elsewhere, with

dialysis patients in this country getting doses more than twice as high as

their counterparts in Europe. Cancer care shows a similar pattern. American

cancer patients are about three times as likely as those in Europe to get the

drugs, and they receive somewhat higher doses.

The

rebates inevitably encourage use of the drugs, said Michael Sullivan, who for

nine years worked as a business manager for the group of six cancer doctors in

the Pacific Northwest, before losing his job last year. He provided The Times

with documentation that shows the size of the rebates, on the condition that

the group not be identified.

“Personally,

I think rebates should go away,” said Mr. Sullivan, whose father was a

kidney dialysis patient who died of a heart attack while taking one of the

anemia drugs. “The whole problem with it, I guess, is that you’re playing

with people’s health. It’s not the same as buying widgets.”

For

doctors who use less of the drugs, the rebates may make the difference between

losing money on the drugs or breaking even. Mr. Sullivan said that as result

of the rebates from Amgen, the six doctors in his group made about $1.8

million in net profit on the drugs they prescribed.

Unlike

most drugs, the anemia medicines do not come in fixed doses. Therefore,

doctors have great flexibility to increase dosing — and profits. Critics say

that the companies have contributed to the confusion by failing to test

whether lower doses of the medicines might work better than higher doses.

“The

burden of proof is for companies and industry to demonstrate that a drug is

safe at a certain level,” Dr. Ajay Singh, an associate professor at Harvard

Medical School. Dr. Singh headed a clinical trial that indicated last year

that the drugs might be unsafe in kidney patients at commonly used doses.

Known

generically as epoetin and darbepoetin, and often referred to simply as EPO,

the drugs are genetically engineered versions of a human protein that

stimulates the bone marrow to produce more red blood cells and increase the

body’s ability to carry oxygen.

Most

doctors and patients agree the drugs are very helpful for patients when used

to correct severe anemia, which can be debilitating and even life-threatening.

The drugs reduce the need for risky blood transfusions and can give patients

more energy and improve their quality of life.

“We

have transformed the lives of patients with chronic kidney disease,” said Dr.

Norman Muirhead, a professor at the University of Western Ontario who has

given talks and consulted for Amgen and Johnson & Johnson.

But

there is little evidence that the drugs make much difference for patients with

moderate anemia, and federal statistics show that the increased use of the

drugs has not improved survival in dialysis patients. About 23 percent of

American patients on dialysis die each year, a rate that has not changed since

Epogen was introduced.

Anemia

is measured by a patient’s level of hemoglobin, the molecule the body uses

to transport oxygen to its cells. Healthy people have around 14 grams of

hemoglobin per deciliter of blood. Patients with fewer than 12 grams are

considered mildly anemic, and those with fewer than 10 as moderately or

severely anemic.

The

labels on the drugs, as currently approved by the F.D.A., encourage doctors to

aim for a hemoglobin level of 10 to 12. But about half of all dialysis

patients now have their hemoglobin levels raised to above 12.

Critics

of the drugs say their increased use has been driven by profit. DaVita, one of

the two large dialysis chains, and the most aggressive user of epoetin, gets

25 percent of its revenue from the anemia drugs — and even more of its

profit, according to some analysts.

Dr.

David Van Wyck, senior associate to the chief medical officer of DaVita, said

the company did not overuse the medicines.

Doctors

determine how much to use, Dr. Van Wyck said. “To say that somebody is

encouraging a doc to use more EPO is just outrageous.”

Although

the safety debate has heated up only recently, the first sign that the drugs

might be dangerous came more than a decade ago. That evidence emerged in a

trial sponsored by Amgen that was set up to show that dialysis patients would

benefit from having their hemoglobin raised to 14, the level in a healthy

person.

But

the trial, which was stopped in 1996, found that patients in that group had

more deaths and heart attacks than a group treated with a hemoglobin goal of

10.

That

trial should have discouraged doctors from using too much epoetin and

encouraged Amgen to study the risks further, said Dr. Steven Fishbane, a

nephrologist at Winthrop-University Hospital on Long Island.

Instead,

use of epoetin continued to soar. No one conducted a trial to determine

whether the optimal hemoglobin target in kidney patients might be 10 or 11,

instead of 12 or 13 — a crucial question that remains unanswered even today.

Dr.

Anatole Besarab of the Henry Ford Hospital in Michigan, the lead author of the

study that was stopped in 1996, said that Amgen and Johnson & Johnson had

little incentive to conduct such a trial.

Dr.

Robert M. Brenner, head of nephrology medical affairs for Amgen, said there

was ample data from previous trials showing that treating up to hemoglobin of

12 was safe and effective.

Some

hospitals and doctors have used epoetin more conservatively than the big

dialysis chains.

Dr.

Ronald A. Paulus, chief health technology officer at Geisinger Health System,

a nonprofit group that includes three hospitals in Pennsylvania, said

Geisinger had lowered its use of epoetin by 40 percent. Its doctors did do so

simply by monitoring patients more closely and giving them more iron, without

which the body cannot make hemoglobin.

Dr.

N. D. Vaziri, the chief of nephrology at the University of California, Irvine,

said some clinics had been too aggressive about giving extremely high doses of

epoetin to people who did not initially respond to lower levels. The United

States is virtually the only country in which patients get super-high doses.

“You

create a toxicity situation,” said Dr. Vaziri, who has done studies in

animals showing how epoetin contributes to hypertension and blood clots.

In

cancer patients, concerns were raised in 2003 by clinical trials meant to show

that raising hemoglobin to high levels would make chemotherapy or radiation

therapy more effective. Instead, several trials showed the drugs appeared to

worsen cancer or hasten death, although one recent study by Amgen showed that

its drug Aranesp had no effect on patient survival.

The

conflicting studies are among the issues the F.D.A. advisory committee is

expected to discuss tomorrow. Already, some cancer doctors are moderating

their use of the anemia drugs.

Dr.

Peter Eisenberg, an oncologist in Marin County, Calif., said many doctors had

been induced to use more epoetin by the financial incentives and the belief

that the drug was helpful.

“The

deal was so good,” he said. “The indication was so clear and the downside

was so small that docs just worked it into their practice easily.

“Now

it’s much scarier than that,” he said. “We could really be doing harm.”

(Mei 2007) (Opm. Zo zie je maar waar we naar toe gaan in de Westerse gezondheidszorg. Dan is het toch beter de adviezen op deze site proberen op te volgen. Voor zij die denken dat dit alleen maar Amerikaanse toestanden zijn: eerdere onderzoeken laat zien dat in Nederland jaarlijks 1 miljard euro door de farmaceutische industrie uitgegeven wordt aan "marketing". )

09-05-2007